Saturday 18 November 2006

As we leave the forest the track levels, dips, and rises again towards the  and are often greeted with exclamations of recognition and delight. Mr S and Dr M — the teacher and the doctor — are well known and clearly appreciated here. Mr S has been coming here since 1961; he lived here for 2–3 years and set up the school. He left, he says, because he couldn’t stand the ignorance — I think he means the clinging to superstitions — and he tells me that in remote villages difficult to access, 95% of the work is done by the women, while the men mostly sit around “drinking, playing cards, or taking narcotics.” But today, everyone, men included seems to be out in the fields, working.

and are often greeted with exclamations of recognition and delight. Mr S and Dr M — the teacher and the doctor — are well known and clearly appreciated here. Mr S has been coming here since 1961; he lived here for 2–3 years and set up the school. He left, he says, because he couldn’t stand the ignorance — I think he means the clinging to superstitions — and he tells me that in remote villages difficult to access, 95% of the work is done by the women, while the men mostly sit around “drinking, playing cards, or taking narcotics.” But today, everyone, men included seems to be out in the fields, working.

We stop and are welcomed at a house where a family’s threshing amaranth, the man driving two slow cattle beasts around in circles over the strewn stalks. We’re shown inside, through a tiny door, into a pastel green room with massive, thick, stone walls and a small window. Two beds, posters on the walls. Shiva. We’re given tea by the daughter; it has a pleasant tang, a kind of sharpness and I guess it’s sweetened with honey.

More tea soon after — this is to become a pattern — where Mr S is greeted with what can only be described as joy.  He introduces me to an ancient-looking, tiny man who takes my hand between his and gives me a wonderful, beaming, gap-toothed smile. His face isn’t wrinkled — it’s deeply creased, and he looks to be at least in his 80s. Mr S later tells me he’s 65, the same age as him.

He introduces me to an ancient-looking, tiny man who takes my hand between his and gives me a wonderful, beaming, gap-toothed smile. His face isn’t wrinkled — it’s deeply creased, and he looks to be at least in his 80s. Mr S later tells me he’s 65, the same age as him.

...

Beyond Urgam we stop to visit the temple at Kolpeshwar. As usual, I’m reluctant to intrude, but with Mr S’s encouragement — insistence, in fact — I visit the shrine. A small, dark cave, lit by flame and with a beautiful incense from a small array of smouldering sticks. The centre, the focus, is a stone about the size of a human head. The power here is astonishing — there’s something, some kind of energy or force, something that feels ageless, profound. For the first time in

The saddhu distributes photo albums for us to inspect. One of the main subjects is a yogi who lived upriver for eight or nine years, and for 30 years kept his right arm raised above his head. Several photos show how his fingernails, uncut for that period, grew down across his palm and coiled around his wrist. I can’t help thinking, “Why?” and am reminded of Peter Matthiessen’s mention of the sage who reputedly wept when he heard of the man who had spent 30 years learning to walk on water when the ferryman could have taken him across the river for a small coin.

years kept his right arm raised above his head. Several photos show how his fingernails, uncut for that period, grew down across his palm and coiled around his wrist. I can’t help thinking, “Why?” and am reminded of Peter Matthiessen’s mention of the sage who reputedly wept when he heard of the man who had spent 30 years learning to walk on water when the ferryman could have taken him across the river for a small coin.

We walk back across the river on a footbridge. From there, the remains of a stone-paved road, now strewn with fallen leaves, follows the river through the autumn forest. This is virgin forest says Mr S, who used to walk here often when he lived at Urgam. He tells me some of the animals that lived here; animals he’s seen on his walks: deer, hogs, bear. Leopards. When we return through the lower forest below Urgam in the late evening he explains it’s important in the mornings and evenings always to walk with at least one other person because of the bears. They don’t usually attack people, but it is not unknown.

I look around at the forest, denser here than lower down, the trees taller, the understorey more vigorous. It’s easy to believe we’re getting beyond the range of daily human activity, that we might indeed see a large shape leap or crash away deeper into the forest — but we’re walking on the remains of a road. “Virgin” is a labile word, its context in

that we might indeed see a large shape leap or crash away deeper into the forest — but we’re walking on the remains of a road. “Virgin” is a labile word, its context in

But, despite the sense of leaving other humans behind, we come to a rough footbridge — branches laid side by side on parallel poles which span the stream; one or two flat rocks added; a rickety but effective structure — and on the far bank, four buffalo browse. The human world returns, and with it a trace of melancholy.

Nevertheless, we’ve arrived. A short way on we follow a track up a bank and through a heavy, badly leaning but functional gate in a dry stone wall overgrown with tall weeds and small shrubs. Inside: a small hut, plastered the colour of clay, the doorway and eaves blackened by smoke; in front of the hut, an area paved with flat stones and partly covered with blankets; next to it a tap trickling clear water into a bright steel pot, the water overflowing onto the stone slab beneath. A small vegetable garden, with dark soil, bright green cabbage seedlings and no weeds; nearby, a small forest of spindly, wild hemp, with only a few leaves left.

Sitting on the blankets in front of the hut, a small man with a dense, mostly white, unkempt beard, his hair curled in a topknot, a dun-coloured blanket wrapped around him, smiles at us. This is the monk we have come to visit: Maharj Raman Giri.

The monk — Mr S’s term; I’d say saddhu but only because he looks like one — speaks softly, and the creases around his eyes suggest that behind his smoke-stained beard he’s smiling most of the time. Some people have what’s usually described as a “presence”, an air of something significant, out of the ordinary — even the sceptical, I suspect, voice their scepticism because they’re aware of this presence and feel compelled to question it out of their own insecurity. I might be wrong. This man, however, has that presence, a kind of attentive serenity with a quiet, unaffected humour. How can I tell this? Perhaps from the laughter during the conversation, and the way he laughs, but I really don’t know how I know — I just know.

The monk — Mr S’s term; I’d say saddhu but only because he looks like one — speaks softly, and the creases around his eyes suggest that behind his smoke-stained beard he’s smiling most of the time. Some people have what’s usually described as a “presence”, an air of something significant, out of the ordinary — even the sceptical, I suspect, voice their scepticism because they’re aware of this presence and feel compelled to question it out of their own insecurity. I might be wrong. This man, however, has that presence, a kind of attentive serenity with a quiet, unaffected humour. How can I tell this? Perhaps from the laughter during the conversation, and the way he laughs, but I really don’t know how I know — I just know.In fact, he speaks very good English, better than anyone I’ve met so far in

But, “Bears,” he says, “this is bear country.” His eyes sparkle. How long has he lived here? Six or seven years, but he visited here for another six or seven before that. Over that period, what changes has he noticed in the numbers of animals? He shrugs slightly.

But, “Bears,” he says, “this is bear country.” His eyes sparkle. How long has he lived here? Six or seven years, but he visited here for another six or seven before that. Over that period, what changes has he noticed in the numbers of animals? He shrugs slightly.“The same types of animals, but fewer of them.”

Outside, voices, some kind of activity. Villagers have arrived to cut hay along the river banks. Each year they come more often, and go further up the river, and what’s wild, I think, moves further back. Eventually there will be nowhere left to which to retreat. I think of the monk as well as the deer, the bears, and the leopard, which might already be gone.

...

After chai, Maharj prepares food, rinsing a few handfuls of mixed dahl and placing it in his small brass pot with water. The pot sits on a battered, blackened, trivet over a small fire fed by gradually moving long, dry branches further into the coals. A small flame, and a little smoke curls up and flows out the door. The hut has no chimney. He cooks cabbage with herbs and chillies — a kind of cabbage curry — and an enormous pot of rice, while the two friends who have accompanied Dr M, Mr S, and me prepare radish and select dangerous chillies as accompaniments. I talk a little more with Maharj, known to the local people as “Engineer Baba” because he has a first class Masters degree in mechanical engineering. He asks me about

The food ready, Maharj dishes it onto steel plates for us. Vast amounts of rice, a good ladleful of dahl and a couple of ladles of the cabbage curry. Mr S protests at the amount and is humoured — I also protest but Maharj just grins at me, says, “By the time you’re halfway down that hill, you’ll need it,” and keeps ladling. It’s good — very good — and I eat it all. And it gets me down the hill.

Dr M has seconds, but as Maharj dishes it, the doctor says something which I assume means, “Hey, hey, that’s enough!” But Maharj just smiles, mutters,  and adds another large spatula scoop of rice.

and adds another large spatula scoop of rice.

Laughing, I say, “That’s what my mother used to do. We’d say, ‘No more,’ so she’d give us two more spoonfuls.”

Maharj leans back, laughing.

When I’ve finished I put down my plate and say, “That was very good, thankyou.” He gestures at us and points out that we brought all the food with us.

“Well, it was very well cooked.”

He says nothing, but smiles and nods towards the fire.

Dr M’s keen for a group photo, so I take two when they line up outside the hut. As usual, the second’s better. This is usually true — the first photo’s formal, everyone, or the individual, looking serious, then they relax and you’re more likely to get the smiles. I say goodbye to Engineer Baba and thank him, genuinely.

“You’re always welcome here,” he says. “Come whenever you like. Stay a few days.”

Photos (click to enlarge them):

1. The man at Urgam, said by Mr S to be 65.

2. Threshing amaranth at Urgam.

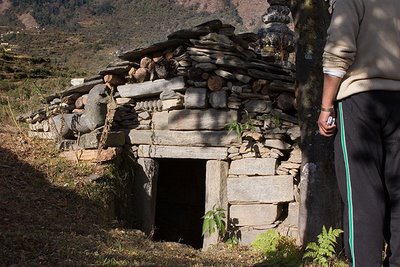

3. This small temple at Urgam, I was told, dates back several thousand years.

4. Amaranth thresher.

5. Part of lunch.

6. A typical house in the area.

7. Engineer Baba, Maharj Raman Giri. (Pronounced "Maharaj").

Photos and words © 2006 Pete McGregor

11 comments:

Great stuff Pete, enjoyed it.

The perfect meal. Simple ingredients and good people to cook it and then sit down and share it.

Pete, your words and images had me sitting there taking it all in and wanting to return.

Thankyou.

Thanks, once more, Pete, for taking the time and making the effort to share all these things with us.

I've met people who emanate the kind of presence you speak of and though I can't put my finger on it, it is truly remarkable. Your story managed to impart a sense of that presence in Engineer Baba, and that last photo absolutely does. Thanks.

You have so beautifully shared these moments with us, pete. Your observations are so perfectly detailed. I could almost taste that dahl and cabbage curry.

I have often wondered about the huge population in India and its impact on the environment. I am waiting, as you are, for the time you will find yourself away and apart from people and into the wild places.

You mentioned that Maharj has a presence... well, your photo of him very strongly brings that across; you can see it in his eyes and the way he smiles at the camera. Even the way the other man blurs in his movement around him... as if Maharj is standing still while everyon else bustles about.

...it seems as if you realy enjoy your time "Out of Pohangina Valley".

Very good Pete, you are still where you are; it looks for me as nothing, -except the place..., has changed.

Hey there Pete :-)

The phrase "wherever you are, be there" springs to mind. You have the rare knack of being able to clothe yourself in the immediate happenings of your environment. And that means we are treated to the brilliance of your photography and words as a result of that. Thank you for bringing the world, and you, back into our space!

Enjoy the journey to the place of non-humans - and take very good care of yourself.

from KSG/Linda

Pete--delightful as usual. Thanks much.

As always Pete superlatives fail. Happy that you've managed to find some computer time amongst your great adventure, to share some of it with us.

Pete, just letting you know ( although I am sure you have more important things on your mind right now!), that I have linked your site on my blog as a 'Christmas gift', Hope that's ok with you.

Travel well.

Post a Comment