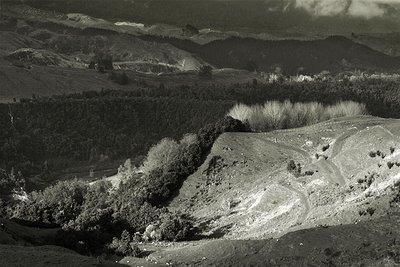

Green hills and long shadows; the morning sun cutting across dark gullies, lighting ridgelines and revealing the texture of the land. In the distance, hazy rain, luminous beneath dark cloud, and beyond, a glimpse of snow rising towards the Ngamoko Range. We look across to where the Pohangina turns East and disappears into the Ruahine Range. I feel as if the land's offering me a gift: the chance to show Tony the nature of this place.

beneath dark cloud, and beyond, a glimpse of snow rising towards the Ngamoko Range. We look across to where the Pohangina turns East and disappears into the Ruahine Range. I feel as if the land's offering me a gift: the chance to show Tony the nature of this place.

He's busy with tripods and graduated filters and a camera the size of a campervan. I'm the last person he's visiting during a month of travelling the North Island, meeting friends, photographing, interviewing, exploring places he’s never been, getting snowed in, surviving a succession of southerly storms—but perhaps most of all, coming to understand more about what he does. Why he does it. Why he photographs. You can see it in his photos; you can feel something in them. He tries to explain it, and the phrase “the wairua of the land” comes up several times. It’s difficult to translate. “Wairua” is sometimes synonymised with “spirit”, but that English word has slightly pejorative connotations. Another friend recently pointed out how, as soon as you mention the word “spiritual”, you’re sidelined; you’re grouped with the fringe dwellers—a candle seen as a fire hazard not a means of illumination. At best, decision makers will treat you as another annoyance needing to be accommodated. Besides, “spirit” doesn’t quite seem to do justice to the concept, although I admit to not understanding it well enough to claim any authority.

We detour up Takapari Road, crunching and squelching slowly in four wheel drive up towards the  bushline and the Forest Park boundary. Four other vehicles occupy the road end. A guy and a pre-teen boy with a camo-pattern high-viz beanie wander around. Just looking, I think. The ground’s half covered with slushy snow and the wind’s like steel on a Arctic beach. But the light is simply astonishing; streaming in angled beams from wild cloud, drifting in brilliant patches across dark hill country far below, the river shining, distant arcs of wet road gleaming.

bushline and the Forest Park boundary. Four other vehicles occupy the road end. A guy and a pre-teen boy with a camo-pattern high-viz beanie wander around. Just looking, I think. The ground’s half covered with slushy snow and the wind’s like steel on a Arctic beach. But the light is simply astonishing; streaming in angled beams from wild cloud, drifting in brilliant patches across dark hill country far below, the river shining, distant arcs of wet road gleaming.

Later, Tony tries again to explain what he means by “the wairua of the land”. He mentions how he often senses a kind of melancholy in the land; not grief, more like a gentle and strangely beautiful sadness. I’m sure I know what he’s getting at, and wonder whether he’s come across the term “wabi sabi”. He hasn’t, but when I try to articulate it, I can’t. I stumble over words, I cast about looking for examples or analogies, but they’re elusive. Now, days later, I can suggest that it’s like walking that fine line between joy and loneliness, akin to an existential awareness but without the angst, and lacking the intellectual pretense. But those are just words, and  I suspect the concept of wabi sabi is further confirmation that Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle has corollaries far removed from quantum mechanics—in this case, the closer you get to defining wabi sabi, the further you move from its essence. This requires tacit understanding; it’s what I know but can’t say. The closest you can come to hearing it articulated is through a poem. Through haiku. Through the quality of art.

I suspect the concept of wabi sabi is further confirmation that Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle has corollaries far removed from quantum mechanics—in this case, the closer you get to defining wabi sabi, the further you move from its essence. This requires tacit understanding; it’s what I know but can’t say. The closest you can come to hearing it articulated is through a poem. Through haiku. Through the quality of art.

And, perhaps especially, through a photograph; one taken by someone open to what the land says, or sings. Someone who not only hears, but listens; not only looks, but sees. Someone, I suspect, not separate from the land.

Photos (click on 1–3 for a larger image):

1. Pohangina Valley, looking towards the Ngamoko Range, from Takapari Road.

2. Pohangina Valley and southern Ruahine Range from Utuwai.

3. Farmland near Utuwai, Pohangina Valley.

4. Rain coming in, Utuwai, Pohangina Valley.

Photos and words © 2006 Pete McGregor

29 comments:

there are concepts that defy translation into English. English is a practical language; it has little room for concepts like "wairua" or "wabi sabi." Looking at the photographs attached to this post of yours conveys the true meaning of these concepts. Getting out in the land does as well. I'm glad I found your blog, Pete.

Incredibly stunningly beautiful, per usual. Thanks.

I suspect it isn't just english, that one culture's essential or core concepts don't translate well through radically different cultures.

Many concepts are just plain hard to define, even within their proper cultural concept. Look at Zen's koan and riddles.

Once again Pete a masterful job. It is getting difficult to find enough superlatives to talk about your writing.

I can only echo Clare's last sentence Pete, and add "and pictures" on the end.

Urck. I'll pass on the mutual backscrubbing and hand-holding here. Having stumbled upon this, I feel compelled to buck the sticky trend of honeyed comments and say that I think your poems are embarrassingly bad and this site an excersise in self-congratulatory egoism. Indeed, is there anything more egotistical than frenetically advertsising the 'wonders' and 'depths' of your soul, and clambering for as much attention as possible? "Oh look how deep am I!" Is this not what you are yelling at the listener?

After this paean of self-indulgence and raucous mirror-kissing sensitivity, I'm driven to repeat wise words: 'one of the beauties of the landscape is that it is SILENT'.

Wow, that was deep.

NOTE TO REGULAR READERS: Please don’t respond to the comment by “Adrian”. I don’t know whether he/she is a troll or not, but the beliefs might be genuinely held and she/he is entitled to them. All I’ll say is that I’d have preferred the comment to have been constructive and it would have been nice if it hadn’t been anonymous. No harm done; let’s just leave it at that. :^)

Divajood: Interesting point; I hadn't really thought much about English being a language primarily concerned with practical functions. Something to think about — thanks!

Nuthatch: Much appreciated; thankyou :^)

Clare: Yes, good point about concepts often not transferring easily between cultures. I guess language is both a product and determinant of culture, so it's not surprising that translation can be so difficult — especially when the words are so hard to find within the culture of origin. And thanks for the encouragement :^)

Cheers Duncan; thankyou :^)

Pete, I have often struggled with a descriptive for the "sense" the land conveys...and you nailed it for me utterly. "....a gentle and strangely beautiful sadness..." Your piece and the photographs leave me feeling breathless and aware ... of something.... I am reluctant to define it, being more inclined to simply feel it. And I thank you for the entire experience! :-D

Another way to express wairua? Yes it's not easy. Mauri is another I couldn't translate. Still, reading Elsdon Best started me toward understanding.

But you do have a way of capturing the spirit in your images...

you touch on something i have experienced so many times and also struggle to express. it is a flow of something tangible coming from the land. and the longer one is in the presence of it the more palpable it becomes. your description of a beautiful sadness comes about as close as anything i have found. it's a deep in the heart kind of emotion.

...(sorry hit enter by mistake)that fills your images. they are gorgeous.

Once again, I leave bedazzled--and longing for New Zealand.

Pete, can I ask a technical question? Are you shooting digital, or film? Filters, or no? I just got a digital SLR, still learning it, and don't know if I need to be using anything -- do I want a polarizing filter? Other stuff?

Thanks!

Pete-- I don't think I've ever read it more eloquently expressed than this: Existential awareness without the angst. There is so much in that moment of realization, when you fully embrace the ephemeral quality and nature of everything. A photograph comes close to capturing a moment that has already past, and perhaps we love photography because it does it without having to use words like spirit. A beautiful piece of writing here, Pete.

Pete - you and Tony have written great complementary pieces about wabi sabi. This is a concept I've been familiar with for a while, but for which I hadn't known the term.

You and Clare write about the difficulty of transferring concepts across culture and I was thinking about this in relation to wabi sabi. Historical experience must profoundly shape culture and language. We of "the West" have a culture that evolved in - generally speaking - a more stable geographical area of the world than the Japanese. Maybe this is why we didn't develop the same acute awareness of natural forces. On the other hand, Japanese culture has evolved on geologically unstable islands which are also affected every year by typhoons, usually with at least some deaths occurring. During the rainy season there can be landslips, sometimes causing deaths. There are active volcanoes. Snow falls heavily every year in some regions. No wonder, with having earthquake, flood and fire as part of the natural order of things, the Japanese have developed a sense of impermanence and the melancholy implicit in wabi sabi.

Sakura, cherry-blossom, is seen as a symbol of this - and this is where I first came across wabi sabi. (So, not in a haiku, but a flower!) Edward Fowler, in the compilation "One Hundred Things Japanese", says the quintessential nature of sakura is "the haunting theme of impermanence... No sooner do they reach their peak of efflorescence than the blossoms fall, shaken by a capricious gust, scattered by a chilly spring rain. They fall mercifully, sadly, eloquently: mercifully, because more than a few days of cherry-blossom viewing would be exhausting; sadly, because the scattering petals traditionally call to mind those whose lives have been cut short; eloquently, because the short-lived blossoms affirm most profoundly the Japanese aesthetic: that what is beautiful in nature and in human life rarely lasts, that evanescence itself is a thing of beauty, and that nostalgic memories of what has fallen at the height of glory are the most beautiful of all."

Tony says that few landscape photographers seem to be aware of wairua, the spirit of the land. Is this because most have come from the culture of the West? However, it is something our indigenous people recognise. Is this because they have lived here longer and, both before they came and after, have lived closer to the land in regions more subject to natural disasters than Europe is?

Stunning images, Pete. I think black and white can often convey feeling that colour doesn't, especially in these days when our eyes are bombarded with vibrantly coloured images from all sides.

KSG: Thankyou :^) When Tony mentioned that particular 'melancholy' it triggered a recognition of what I'd also felt so often; in much the same way as I'd recognised it in what I'd read years ago about wabi and sabi (I encountered them as separate words then). And understanding it really seems possible only through 'feeling' it.

Flaneur: Yes, 'Mauri' seems even more resistant to translation. Thanks for the remark about the photos, too — it's always good to hear someone else has glimpsed what I did. Enjoy that weather down there, too ;^)

YSWolf: I'm very pleased the photos work so well for you. It suggests the idea described by Tony as "the wairua of the land" is universal: the phrase might be unique to Aotearoa, but what it attempts to express is something we can all share if we're open to it.

Patry: Thanks! :^) NZ's a very special place, and I'm lucky to live in a very special part of it.

Divajood: OK; I've used a digital SLR exclusively since the end of 2004. When I was shooting film I used to use various filters, but since switching to digital I can't recall ever having a filter on any lens. That being said, some people like to keep a UV filter on their lenses to protect the front element; I use the lens cap instead. A polarising filter can help if you want to reduce distracting reflections (e.g., from wet foliage), but it's not as necessary for increasing saturation (intensity of colour) because you can do that later on the computer. While you're learning, stick with the basic stuff; get to know the camera and lenses well before you start trying extra things. The two recommendations I would make are: 1) get heaps of memory and split it between two or more cards in case one falls over; and 2) get at least one spare battery and keep it charged. Why? Because those 2 things will encourage you to take lots of photos, and the more you take, the more you'll learn.

I do strongly recommend Tony's blog (I see you've found it already!). Happy shooting!

Robin: I was pretty sure you'd understand what I was attempting to say — in the photos as well as the words. Thankyou :^)

Peregrina: That's a good thought; how vulnerability to natural forces might alter attitudes and awareness. It certainly has the ring of truth about it. Your comment about black and white photos is interesting too, particularly as Tony suggested some people 'see' in black and white, while others see in colour.

To me the meanest flower that blows can give thoughts that lie too deep for tears…Pete, thank you for introducing your readers to the concept of Wabi sabi which I, for one, had never heard of but have certainly experienced and which informs so much of the literature I teach. Debbie

The pictures and the writing complement one another- and the totality is quite moving.

Debbie, that's such an apt statement; confirmation that the feeling's universal, not just in place, but time. It seems appropriate to add, "For I have learned to look on nature, not as in the hour of thoughtless youth, but hearing oftentimes the still sad music of humanity."

Thanks Debbie; much appreciated.

Chuck: I find images (whether photos or other) and text often compete rather than complement, so I'm very pleased to hear these worked well together. Cheers! :^)

scudy&kimboz: A lovely comment — thanks guys! See you sometime soon :^)

Pete- thanks, in reading this and pausing to contemplate the photos, I have learned a lot today. I have learned there is a word, a concept, for the way I feel when I realize the spring flowers have long since withered, and the land is lush and green in a way it won't be in a month, or even next week. How I ache to stop and hold it all, yet how I feel at the same time a deep sense of calm.

Deb: I think, perhaps for me, the real value of the term is simply that it lets me know that many other people feel the same thing. And every example (like yours) adds something to my understanding of the concept — a process far more powerful than any attempt to define the phrase. Thanks :^)

I saw this post pop up a couple of days ago on Bloglines, Pete, but I delayed coming over to read until I knew I would have the time to do it justice.

For me, the feeling you are describing is indeed a fine line between joy and loneliness ... there is a poignancy in the fact that nothing can be held or retained in what we are seeing at any given moment - only seen, really seen, then released.

Thank you too for the introduction to wabi sabi, which is new to me and which I will follow up.

The photographs are all quite wonderful.

Inspiring. Thank you.

Mary, thanks. This post seems to have connected with many people, and for me it also keeps disclosing other types of connections — I'm thinking in particular of how it seems to touch on the ideas of non-attachment and of whakapapa (roughly, genealogy) and its relationship to place — ideas that superficially seem contradictory, but which, at a deeper level, are in fact consistent. Also, I think your post about your visit to Struell Wells in Ireland worked beautifully to express the ideas I was trying to convey in this post and through the photos. Serendipity? Or synchronicity? Or "coincidence"? Who knows; the important thing is that it happened.

Thanks Mary.

Kia ora Pete:

I just read your blog sbout our time together, and a wonderful thing it is. if I may just chip in a few things......

One of the things that informs my photography is a thing I have felt for some time whenever I am out in the landscape. The reason for my use of wairua has of course much to do with my ethnicity. And I need to make a distinction here between wairua and mauri.

For me mauri is the essence of a place. It is the feeling that comes from a combination of (perhaps)geography, botany/zoology, geology and of course the changes wrought by humans who have dwelt there. Add to that personal felings and a sense of place is engendered.

Wairua on the other hand is all of these and more. I think I may have told you of an experience where I could hear the Land singing. A friend down this way knows exactly what I mean. he has turned it into a musical score. There are places in this country where there is a presence, a feeling of being un-alone. Personally I find it difficult to detect this in the cities, so I need the wild places. Like you.

Wairua can be translated as spirit, but has other layers of understanding, and a spiritual/mystical component that is important to me and informs how, where, and why I photograph.

So call me a nutter.....

Ka kite ano

Thanks Tony. The way you've explained the distinction between wairua and mauri seems intuitively right to me. As for the singing, what immediately springs to mind is the Australian songlines; the idea of singing the world into existence — I suspect it's an essential element of other cultures, too. But I'm even more out of my depth there.

And there's no way I'll call you a nutter, Tony. E hoa sounds better.

E noho ra.

Pete, I love your B/W pics; landscapes are super!

Thanks Mario! :^D

Post a Comment