Sunday 19 November 2006

They’re dynamiting down in the valley again. A sudden boom, the reverberating echo, then a second or

two later the sound of a tremendous fall of rock. What orogenesis and erosion create, we humans seem compelled to modify.

two later the sound of a tremendous fall of rock. What orogenesis and erosion create, we humans seem compelled to modify.Driving to Badrinath three days ago, we looked down to the river, the flow of water substantially subordinate to the size of its bed. Much of the flow, apparently, has been diverted for the Vishnuprayag hydroelectric power project. It’s a familiar story, and I’m reminded strongly of the Whanganui River in New Zealand’s North Island. Both rivers beheaded to provide power. Where does it end? When will the demand for more power cease? When these rivers have all been maimed, will the windmills and solar plants move in? What will limit their spread? I imagine the ridgeline of Elephant Peak lined with churning mills instead of old pines, the Himalayan sun shining not from a turbulent river pouring over washed-clean boulders but from an array of focused mirrors.

I write these words by candlelight because the electrical supply has failed again. As I waited for the agonizingly slow internet connection this afternoon I felt my impatience and frustration as a physical sensation, like anxiety, and had to remind myself to relax; that if I couldn’t achieve as much as I wanted in that half hour, what was the real loss?

Perhaps this is a too-common mistake: to think the solution to an unmet need is to supply the demand rather than remove the want.

Perhaps this is a too-common mistake: to think the solution to an unmet need is to supply the demand rather than remove the want....

Monday 20 November 2006

What makes a life better? What enables a life to be lived with a better sense of accomplishment — “satisfaction” has too much smugness to be a satisfactory word — or delight in the living of that life? Ask anyone here in Joshimath or the nearby villages and the answer’s almost certain to be pragmatic: more reliable electricity, better roads, a safer, more effective supply of clean water. Perhaps more appliances and labour-saving devices, although there seems to be no shortage of small shops selling TVs, DVD players, radios and so on. Perhaps a functional internet? I’m guessing.

Others might take a longer view — better education and easier access to it; some form of minimum wage or other social welfare. What all these sorts of answers have in common is that they assume life will consequently be easier, that there will be less hardship. Does that make life better? Perhaps, if “better” means, as I’ve implied, a greater sense of achievement, these things do not make life better. I think this was one of Nietzsche’s main arguments — that adversity enables us to improve: “What doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger”. But there are different kinds of hardship, and I wonder whether there’s much sense of achievement from simply managing to survive another day. My guess is that the

feeling is one of relief rather than accomplishment; moreover, I suspect the relationship between adversity and improvement is not only non-linear, it’s not even monotonic; in plain language, beyond a certain level, hardship wears you down and weakens you.

feeling is one of relief rather than accomplishment; moreover, I suspect the relationship between adversity and improvement is not only non-linear, it’s not even monotonic; in plain language, beyond a certain level, hardship wears you down and weakens you.I wondered about these things as I lay awake this morning. I wondered because the way life’s lived in the little of India I’ve seen so far seems so hard. Borderline, in fact, for many people. I wondered what would make it better; what, if anything, I could do — or anyone could do. But I also realized that the ramifications of well-intentioned actions can be unexpected and undesirable, especially when based on little knowledge and even less understanding. And, also, that one person’s good intention is another person’s meddling.

...

Wednesday 22 November 2006

When I step outside into the dawn, the world has changed. I’ve become accustomed to the brilliant, cloudless Himalayan sky, sun touching the summits, but this morning dark cloud and misty rain hang about the peaks and drift into ravines; the whole sky’s heavily overcast. It should seem oppressive and ominous but it’s magnificent, a vision from the mind of William Blake. Crows wheel and caw in the cold air; behind them, nothing but space and height and then mountains swirling with mist, precipices edged with old pines, deep ravines disappearing into the gloom. Do you get used to these things; how long, if ever, does it take before you stop seeing these things — before they stop you in your tracks? How much conscious attention does it take to continue noticing and appreciating them? Surely this depends on the person, on who you are — if your attention focuses on cutting another load of hay, or drying the laundry, or trying to stay warm, you might notice birds flying in drizzle but fail to appreciate the immanence in the slow, strong grace of crows circling against that vast landscape. On the other hand, perhaps I don’t truly appreciate the difficulty of weather like this — Mr S

tells me it’s 4°C and the barometer’s falling — for those cutting hay, doing laundry, or facing a hard, bitter winter. I do have some inkling, though, as I write with slow, cold, mittened hands, sip hot water with biscuits, and huddle in a blanket in an unheated room, trying to keep warm.

tells me it’s 4°C and the barometer’s falling — for those cutting hay, doing laundry, or facing a hard, bitter winter. I do have some inkling, though, as I write with slow, cold, mittened hands, sip hot water with biscuits, and huddle in a blanket in an unheated room, trying to keep warm....

Thursday 23 November 2006

At Mirag, kids play cricket in a small courtyard and laugh after I’ve passed by. An elderly woman gives us tea in bone china cups, with biscuits, and like so many people I’ve met here, responds warmly to my “namaste”, my hands pressed together in front of my chest. It’s the same with the elderly man we meet as we leave — his eyes sparkle as he beams at me, leaning on his stick. And Mirag’s gardens are neat and fertile; cauliflowers carefully weeded, a plot of marigolds, things indicating knowledge and attention — and a great deal of hard work. A simple life, but hard — or a hard life, but simple? Given the choice, which would you choose: hardship or ease, simplicity or complexity?

...

Saturday 25 November 2006

A common road sign here says, "Life is journey Complete it." At Nandprayag I look down from the bus window to the ghats at the confluence — the prayag — where a small cluster of people watches a massive fire among the boulders by the water's edge. Nearby, on a raised structure, another figure, shrouded in black, waits for the fire. These lives have been completed, or, according to the prevalent belief system here, are undergoing transformation.

If I were to be reborn as an animal, I think I'd like to be reincarnated as a bird. Closer to Joshimath, what I

think are white-backed vultures soar high around the precipitous bluffs; I have to lean closer to the window and look up to see the birds circling. One flies close to the mountainside, its shadow distinct, following close beneath and slightly behind the bird in the strong morning sun. We're like the shadows of birds, trapped on the ground, but even more constrained — to go where that bird's shadow traversed so easily would require enormous skill, artificial aids like ropes and climbing protection, and the mental ability to deal with terrifying exposure. My years of climbing have accustomed me to some degree of exposure, but even so I feel a few rushes of adrenaline when I look down and see not road but a sheer drop to the gorge far below. I tell myself the driver does this everyday; the wheels aren't as close to the edge as they seem; and I remind myself to think like a bird — to soar out over the abyss and enjoy the freedom, the ability to cross in minutes by wing what would take us half a day on foot, and probably using hands much of the time.

think are white-backed vultures soar high around the precipitous bluffs; I have to lean closer to the window and look up to see the birds circling. One flies close to the mountainside, its shadow distinct, following close beneath and slightly behind the bird in the strong morning sun. We're like the shadows of birds, trapped on the ground, but even more constrained — to go where that bird's shadow traversed so easily would require enormous skill, artificial aids like ropes and climbing protection, and the mental ability to deal with terrifying exposure. My years of climbing have accustomed me to some degree of exposure, but even so I feel a few rushes of adrenaline when I look down and see not road but a sheer drop to the gorge far below. I tell myself the driver does this everyday; the wheels aren't as close to the edge as they seem; and I remind myself to think like a bird — to soar out over the abyss and enjoy the freedom, the ability to cross in minutes by wing what would take us half a day on foot, and probably using hands much of the time....

Down in the river at Karanprayag, men have been breaking rocks by hand, pounding boulders with sledgehammers. Another man sits on a huge mound of fractured pieces, breaking them down with a hammer into smaller fragments. This happens everywhere I've been in India. At the end of each day, what sense of accomplishment might you feel from such a job, knowing it will be the same tomorrow and perhaps for the rest of your life; that there will always be more need for broken rock and there will always be more rock to break? Is it enough to say, "This is what I do," the way others say, "I write," or, "I photograph," knowing there will always be more to write, always more to photograph?

If your life is a journey, where is the breaking of rock taking you, and what will you look back on when you're about to complete it?

...

Sunday 26 November 2006

Mid morning, the early winter sun lighting the valley of the Ata Gad, a swift, powerful river flowing to its confluence

with the Alaknanda at Karanprayag. Steep, high mountainsides drop to the river; they're sparsely forested with conifers, and, amazingly, here and there I see villages perched near the ridgetops. How do you live in such a landscape? A visit to the valley bottom must be a major undertaking. This is country for wild animals: birds like the lammergeier I see patrolling near the ridgetop; once again its shadow follows as if unwilling to separate from the bird.

with the Alaknanda at Karanprayag. Steep, high mountainsides drop to the river; they're sparsely forested with conifers, and, amazingly, here and there I see villages perched near the ridgetops. How do you live in such a landscape? A visit to the valley bottom must be a major undertaking. This is country for wild animals: birds like the lammergeier I see patrolling near the ridgetop; once again its shadow follows as if unwilling to separate from the bird.I look down from the summit to the river, wondering about the fish living there. The mahseer has a reputation for being a fierce fighter when hooked, and this seems appropriate for this fierce river. The mahseer, the river, the landscape — the word "uncompromising" springs to mind.

And the people? I don't know them well enough — I hardly know them at all — yet from what I've seen, there must be a toughness there, a will to survive. In Karanprayag I saw two porters carrying a lounge suite; one carried two stacked, upholstered armchairs, the other an enormous sofa, and they walked along the road with these immense loads on their backs, with no aids other than a tump line around the forehead. I've seen others carrying staggering loads of bricks or broken stone, two bags of cement, enormous sacks of potatoes or onions — there seems to be nothing they can't carry. Yet they're only small, these porters; if I stood face to

face with one, he'd look directly at my chest, possibly not even that high. The women, too: small like the men, and like the men they carry enormous loads. Up ahead, two haystacks move slowly along the road with a slight side to side, rocking motion; as we draw closer, I see the legs beneath the stacks, a slow plodding; the women bent over under their loads. Day after day they do this; they've carried these loads for centuries, perhaps millennia. Again, the question — what have you accomplished at the end of your days?

face with one, he'd look directly at my chest, possibly not even that high. The women, too: small like the men, and like the men they carry enormous loads. Up ahead, two haystacks move slowly along the road with a slight side to side, rocking motion; as we draw closer, I see the legs beneath the stacks, a slow plodding; the women bent over under their loads. Day after day they do this; they've carried these loads for centuries, perhaps millennia. Again, the question — what have you accomplished at the end of your days?Perhaps, if they knew me and knew my life, they might ask me the same question. If I had an answer for them, it would probably mention the creation of something new, and something that shares a life. What I'm doing now, I trust, will be part of that accomplishment.

...

At Baijnath an old man wanders back and forth beside the bus, an air of nervousness about him. Anxiety. He wears a pale, roughly knitted woollen jersey, grubby about the hem and cuffs, dun coloured loose trousers, old sneakers, a pale grey, well worn pundit's cap. Back and forth, carrying a woven plastic sack one third full of something heavy over his shoulder. He's slightly taller and noticeably thinner than most, so his clothes hang on him. Finally he sits on some steps leading to a small, second story house, but he's only there for a few minutes before an old woman comes

down the steps, wanting to get past. She shoos him away and he gets quickly to his feet and goes and sits in front of a stall. He puts his hands to his cheeks, rubs his palms over his face, hides behind them. He is a man stripped of all self-assurance, as if this is an alien environment. He looks about, this way and that, unwilling to let his gaze settle — perhaps because, if he did, he would be noticed.

down the steps, wanting to get past. She shoos him away and he gets quickly to his feet and goes and sits in front of a stall. He puts his hands to his cheeks, rubs his palms over his face, hides behind them. He is a man stripped of all self-assurance, as if this is an alien environment. He looks about, this way and that, unwilling to let his gaze settle — perhaps because, if he did, he would be noticed....

Kumaon's lower than Garhwal, the landscape more hilly than mountainous, the forest denser and more extensive. Presumably because of the gentler topography, the terraced areas are larger and more abundant; another consequence is that it's possible to see much further — as the bus gains height, the views open up: huge vistas over valleys and hills. Then, behind the furthermost, forested hills, the summits of the Himalaya, white with brilliant snow. At first, just one or two peaks, then a few more, and connecting ridges, then, as we move deeper into Kumaon, a great expanse of the Indian Himalaya comes into view. In Garhwal, at Joshimath, Badrinath, and Auli, although much closer to the big peaks, I only on a few occasions felt as if I truly saw the Himalaya; ironically, although I'm so much further away here in Kumaon among the gentler hills, forests, and cultivated lands, I see the Himalaya better. But, in the evening at Kausani, I scan the distant peaks through binoculars, look at the rock, snow, and ice slopes of Trishul, and realise how far I am from being part of that environment — that here I am among my own kind, but also, that I am not.

...

Monday 27 November 2006

Now, in the middle of a bright overcast day, those distant mountains appear, at a cursory glance, dull and flat; most would find them uninspiring.

But look closer, particularly if you have binoculars; let your eyes wander the slopes and ridges and summits, some of which disappear into misty cloud. It's easy to believe there's no one there, that the whole range is silent except for the sounds of things not human — wind, water, rockfall, birds; that it's the home of the tahr and the snow leopard, the lammergeier and flocks of choughs, their red legs and yellow bills bright and new in the old light. It's easy to believe there, among those mountains, you might understand things that can't be articulated; that language would fail to flesh out the bones of Orphic knowledge; that there you might find not the answers, but the right questions.

But look closer, particularly if you have binoculars; let your eyes wander the slopes and ridges and summits, some of which disappear into misty cloud. It's easy to believe there's no one there, that the whole range is silent except for the sounds of things not human — wind, water, rockfall, birds; that it's the home of the tahr and the snow leopard, the lammergeier and flocks of choughs, their red legs and yellow bills bright and new in the old light. It's easy to believe there, among those mountains, you might understand things that can't be articulated; that language would fail to flesh out the bones of Orphic knowledge; that there you might find not the answers, but the right questions.You might go further in, always a little further. Beyond that last blue mountain. What do you seek? Do you even know — and does it matter?

A faded blue flag fluttering in the breeze, a red plastic chair by a grey plastic table on a dull concrete patio. Beyond, past the smoky hills below, past the densely packed towns and villages and the ubiquitous scattered houses, beyond the smouldering rubbish fires and human lives — the veiled Himalaya, and the idea of mountains.

Photos (click to enlarge them):

1. Indian Himalaya from Kausani.

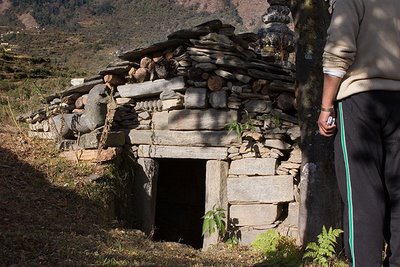

2. One of Mr S's friends.

3. Not sure of the identification of this, but it's the most common conifer high on the slopes above Tapovan.

4. At Rishikesh. Not all who look like this are genuine.

5. Also at Rishikesh. This spider would have been about the size of my open hand. All are genuine.

6. The lower part of Trishul (7120 metres) at sunrise from Kausani.

7. Porter at Naini Tal.

8. Kausani evening.

9. Female snow leopard at Naini Tal zoo. Note: this photo is of a CAPTIVE ANIMAL. I was the only person around; when she noticed me, she stalked and charged me, then played hide and seek. I would far rather have had this privilege in the wild, but it's unlikely I'd be telling you about it now.

Photos and words © 2006 Pete McGregor