On the night of 4 November 1943, four Stirling bombers from 75 Squadron took off from an RAF airbase at Mepal in England on a mission to lay mines in the Baltic Sea. Near Kallerup in Denmark a German JU88 night fighter piloted by Leutnant Karl Rechberger attacked Stirling BF461. Some of the fighter's fire hit home, but Rechberger was wounded in the thigh by return fire from the bomber. Despite the injury he landed safely.

On the night of 4 November 1943, four Stirling bombers from 75 Squadron took off from an RAF airbase at Mepal in England on a mission to lay mines in the Baltic Sea. Near Kallerup in Denmark a German JU88 night fighter piloted by Leutnant Karl Rechberger attacked Stirling BF461. Some of the fighter's fire hit home, but Rechberger was wounded in the thigh by return fire from the bomber. Despite the injury he landed safely.The Stirling wasn't so lucky. The exact nature of the damage will never be known, but it was sufficient to cripple the bomber. Unable to control the doomed plane, pilot Gordon Williams gave the command to bail out.

On hearing the order, the front gunner spun his turret to align it so he could climb back into the bulkhead to retrieve his parachute. Unfortunately, he misaligned the turret; the wind caught and wrenched it and strained the hinges and he found himself trapped in the turret. Fighting panic, he ripped off his helmet and managed to squeeze his head and shoulders through the gap. Suddenly, the plane lurched and he

was thrown through the gap into the bulkhead. He reached for his parachute and tried to clip it on, but by now his fingers were numb and he couldn't tell if the clips had buckled securely. Time was running out. He opened the hatch and lowered his legs into space, then, with a terrific effort of will, released his hold and tumbled into the night sky, away from the crippled bomber. He waited several seconds, freefalling through the night until he was sure his parachute would clear the plane, then pulled the ripcord. A moment later he felt the impact as the parachute opened. The clips were secure.

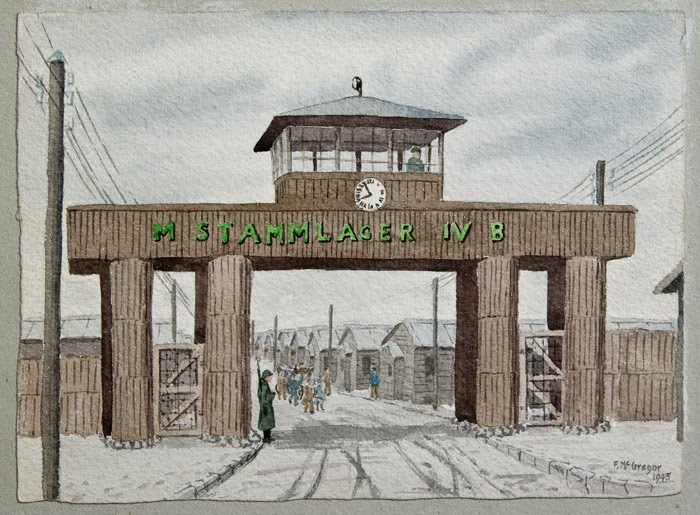

was thrown through the gap into the bulkhead. He reached for his parachute and tried to clip it on, but by now his fingers were numb and he couldn't tell if the clips had buckled securely. Time was running out. He opened the hatch and lowered his legs into space, then, with a terrific effort of will, released his hold and tumbled into the night sky, away from the crippled bomber. He waited several seconds, freefalling through the night until he was sure his parachute would clear the plane, then pulled the ripcord. A moment later he felt the impact as the parachute opened. The clips were secure.With help from local Danes he evaded capture for two days but was finally turned over to the Germans. He spent the remainder of World War II as a Prisoner of War in the huge Stalag IV-B at Mühlburg, about 50 km north of Dresden.

He was my father.

...

When I think about those events of almost 70 years ago, two overriding thoughts come to mind. The first is the sheer insanity of what happened, the second is the absurd improbability that those events and their successors could have led to my sitting here thinking about them.

First the insanity.

I sit in the Celtic, enjoying a beer with a cosmopolitan group of friends: French, US American, Canadian, Irish, English, Spanish—and German. Seventy years ago, I might have been shooting at Marco or dropping bombs on Melanie. Arne might have been forced to throw grenades at me. Christina might have been working on an assembly line manufacturing the night fighter that would shoot my plane from the sky; Barbara perhaps packing boxes of ammunition—bullets to be shot at me. Instead of laughing and hugging each other, helping our team come oh so close to winning the night's quiz, we might have been hiding, waiting for the chance to escape or to kill each other.

How do people rationalise killing people they've never met, have never known? Perhaps it's precisely because of that — because they don't know those people as individuals — that they're able to squeeze a trigger, press a button, or follow — or issue — an order. My father had never travelled overseas before being shipped to

Canada for his training, and, as far as I know, he'd never met anyone from Germany. Apparently, when he released bombs over German cities he felt convinced that what he was doing was utterly justified. Nevertheless, like many of his contemporaries, he seldom spoke about what he'd been through, and by the time I'd grown up enough to discuss it with him, it was too late. But I wonder how he'd have felt if he'd had the opportunity to enjoy friendships with people from the country he viewed as “the enemy”. If he'd talked and laughed and eaten with the person who would eventually become Marco's father or Melanie's mum or Arne's uncle. If someone from Barbara's home town had slept in the shearers' quarters where my father grew up and had sat at the table and eaten roast lamb and peas and tried to describe the huge variety of sausage back home. In short, if he'd had the opportunities and friendships I've been so lucky to enjoy. If, if, if.

Canada for his training, and, as far as I know, he'd never met anyone from Germany. Apparently, when he released bombs over German cities he felt convinced that what he was doing was utterly justified. Nevertheless, like many of his contemporaries, he seldom spoke about what he'd been through, and by the time I'd grown up enough to discuss it with him, it was too late. But I wonder how he'd have felt if he'd had the opportunity to enjoy friendships with people from the country he viewed as “the enemy”. If he'd talked and laughed and eaten with the person who would eventually become Marco's father or Melanie's mum or Arne's uncle. If someone from Barbara's home town had slept in the shearers' quarters where my father grew up and had sat at the table and eaten roast lamb and peas and tried to describe the huge variety of sausage back home. In short, if he'd had the opportunities and friendships I've been so lucky to enjoy. If, if, if.Which brings me to the second thought — the vanishingly small probability that I, writing this, should be here, writing this.

If the turret had jammed with the opening just a little smaller. If the plane hadn't lurched; if the clips on his parachute hadn't been buckled properly. If he'd fallen fatally ill in Stalag IV-B. The list of “ifs” seems infinite, stretching back into the past, before he was born, before his parents were born and so on; and stretching out towards me, as I sit writing this. Once, somewhere in the Southern Alps of New Zealand, he slipped on a mountainside and saved himself by grabbing a small, wiry bush. If a seed hadn't germinated there years before, he'd have fallen over the bluff, probably to his death.

My existence seems an improbability of truly cosmic proportions. Still, I'm here, writing this, and I'm glad. But tell me this. If the chances of any actual event are so infinitesimal, how can wars be so common?

Notes:

1. I'm particularly grateful to Mogens Kruse and Anders Straarup for finding us and providing information additional to Dad's records.

2. Airwar over Denmark by Søren Flensted has a page about Stirling BF461 and its crew.

3. Allied Airmen 1939-45 DK by Anders Straarup includes good information about STI BF461 and all its crew members with many links. If you're keen, you can read Dad's account of the mission and his time in Stalag IV-B by downloading the pdf (70 pages; almost 6 Mb); a smaller pdf (about 600 Kb) is a 7-page account of the week before the camp was liberated. Copyright in both articles resides with the estate of F.E. McGregor.

4. B461 crashed here (thanks to Mogens Kruse for this).

1. I'm particularly grateful to Mogens Kruse and Anders Straarup for finding us and providing information additional to Dad's records.

2. Airwar over Denmark by Søren Flensted has a page about Stirling BF461 and its crew.

3. Allied Airmen 1939-45 DK by Anders Straarup includes good information about STI BF461 and all its crew members with many links. If you're keen, you can read Dad's account of the mission and his time in Stalag IV-B by downloading the pdf (70 pages; almost 6 Mb); a smaller pdf (about 600 Kb) is a 7-page account of the week before the camp was liberated. Copyright in both articles resides with the estate of F.E. McGregor.

4. B461 crashed here (thanks to Mogens Kruse for this).

Photos:

(I photographed these from Dad's albums. Apart from a little cleaning up of spots and scratches they're as close as I can get to the originals.)

1. The crew of Stirling BF461 ("B for Beer"). [Standing, L-R]: W.F. Morice (navigator), W.J. Champion (wireless operator), G.K. Williams (pilot), J. Black (mid-upper gunner), R. Ingray (tail gunner); [Kneeling, L-R]: F.E. McGregor (bomb aimer/front gunner), H. Moffat (engineer).

2. Frank McGregor. I'm not sure of the date of the photo, but assume it was during his training, or perhaps while he was on active service before he was shot down.

3. The main road of Stalag IV-B, from a photo in Frank McGregor's albums.

4. One of his watercolour sketches. It's dated 1945; Stalag IV-B was abandoned by its German guards in April 1945 shortly before a Russian contingent arrived.

(I photographed these from Dad's albums. Apart from a little cleaning up of spots and scratches they're as close as I can get to the originals.)

1. The crew of Stirling BF461 ("B for Beer"). [Standing, L-R]: W.F. Morice (navigator), W.J. Champion (wireless operator), G.K. Williams (pilot), J. Black (mid-upper gunner), R. Ingray (tail gunner); [Kneeling, L-R]: F.E. McGregor (bomb aimer/front gunner), H. Moffat (engineer).

2. Frank McGregor. I'm not sure of the date of the photo, but assume it was during his training, or perhaps while he was on active service before he was shot down.

3. The main road of Stalag IV-B, from a photo in Frank McGregor's albums.

4. One of his watercolour sketches. It's dated 1945; Stalag IV-B was abandoned by its German guards in April 1945 shortly before a Russian contingent arrived.

Photos and original text © 2009 Pete McGregor