soft glow of cloud—cloud visible only because it’s revealed by the light of the city it constrains.

soft glow of cloud—cloud visible only because it’s revealed by the light of the city it constrains. It’s the utter darkness of the harbour that pulls me in. I look at the lights and the dark beneath the line of motorway lights draws my gaze down; down and in. It’s like looking out beyond the boundary of the universe—a feeling I could fall forever, following the countless lives gone before me, vanished, gone, the purest possible aloneness. The terrible longing for extinction. Perhaps this was what Isabelle Eberhardt sought; what she had in mind when she claimed to “have learnt not to look for anything in life but the ecstasy offered by oblivion.” She destroyed herself, but it was a flood—water in the night—that finally took her life [1]. Perhaps the distinction is meaningless. What do you long for?

Dirk sleeps slumped sideways on the sofa. Sometimes he snores and his paws twitch as if he’s making little grabs at dreamed mice. I disturb him, deliberately; stroke his head, feeling the skull beneath the fur. He jerks awake, chirrups loudly and stretches—a long shudder, then he relaxes into a loud, continuous purr. Miep calls at the big patio doors so I open them and she runs inside on silent feet, a warm grey shape with no edges. Straight to her bowl. I stroke her as she eats and I get the sound of a gurgled purr mixed with crunched cat biscuits. It’s impossible to tell when my palm first touches her fur.

I saw an aeroplane fly overhead this afternoon. I looked up from the deck of this house above Eastbourne; looked up into a blue sky streaked with hazy cirrus and watched the belly of the plane, two engines carrying it on a high, slow arc towards the South. A plane flying overhead is always going away from you. I watched as the plane flew on over the gorse hills, out towards the southern horizon; I watched the plane shrink until it became only a brilliant point of light, moving almost imperceptibly. Then it was gone. Down there, down  South, the sky was a grey and orange-brown haze with a faint greenish cast, a smudge of subtle colours. Hogsbacks had begun to form, some towering and massive, others classically curved and elongated, each like a slash in the sky revealing something and somewhere darker through the rent. What do you long for?

South, the sky was a grey and orange-brown haze with a faint greenish cast, a smudge of subtle colours. Hogsbacks had begun to form, some towering and massive, others classically curved and elongated, each like a slash in the sky revealing something and somewhere darker through the rent. What do you long for?

Dirk sat upright, nearby and facing my deck chair. He tucked his feet neatly together, wrapped his tail around them and closed his eyes. A formal patience, waiting to be noticed. I heard the momentary tinkle of a bell, looked around and saw Miep padding toward me. She bumped against my chair, wrapped herself around my leg a couple of times then sat in the same pose as Dirk, closer but with her back to me. A flock of finches flew past, quick, with rapid wingbeats black against the brilliant sea, their voices like the memory of Miep’s bell. Far below, somewhere near the water’s edge, oystercatchers called and I remembered standing outside on a clear, moonless night when I was still in my teens, hearing oystercatchers flying overhead, lost in the darkness, their piping sounding like something from the roof of heaven. There’s a kind of ache in that sound, something that says everything about immensity and timelessness and impermanence; about the appalling and incomprehensible brevity of lives; and about the ridiculous pomposity of too much human activity. What do you long for? The sun went down, the sky began to fade, losing colour, and the wind dropped to a drifting breeze barely strong enough to wrinkle the water. Here and there, glassy patches appeared on the harbour. I looked up into that huge, empty sky and thought, maybe this is why wolves howl.

began to fade, losing colour, and the wind dropped to a drifting breeze barely strong enough to wrinkle the water. Here and there, glassy patches appeared on the harbour. I looked up into that huge, empty sky and thought, maybe this is why wolves howl.

...

Some time after 4 p.m. I packed camera, lenses, binoculars, and notebook and walked down the hill, along the foreshore towards Days Bay. Slowly; thinking how I might get photos of black oystercatchers and gulls, maybe a shag; aware I’d be shooting into the light. Difficult—but if you don’t break the rules you stay safe. After a while and a few experiments I turned back towards Eastbourne. I walked slowly, searching the shore, gazing at details. What was I looking for? I imagined someone asking me the question and wondered how I’d reply. Probably by saying something like, “I don’t know, but I will when I find it.” Can you search for something if you don’t know what it is?

I wondered about the appeal of searching. I know people—blokes, mostly—who seem not to need to look for anything, particularly answers. They seem to know them already. I wonder whether they ever wonder. Am I like that—am I too ready to state facts and deliver answers? The idea that I might be perceived like that filled me with dismay as I picked my way over the wet rocks. I tried to move with grace but felt lumpish and clumsy; an oystercatcher stood balanced on one leg on a barnacle encrusted island of rock and watched me lurch past. What am I looking for? I don’t know, but maybe I will when I find it.

for anything, particularly answers. They seem to know them already. I wonder whether they ever wonder. Am I like that—am I too ready to state facts and deliver answers? The idea that I might be perceived like that filled me with dismay as I picked my way over the wet rocks. I tried to move with grace but felt lumpish and clumsy; an oystercatcher stood balanced on one leg on a barnacle encrusted island of rock and watched me lurch past. What am I looking for? I don’t know, but maybe I will when I find it.

Right then, trying to step carefully in the late afternoon with the sun in my eyes, I wondered whether enlightenment is all it’s cracked up to be. Perhaps I misunderstand it. Perhaps I don’t know what it is. Will I know if I find it? I hopped to another rock, and realised I’m not looking for it—at least, I don’t think I am. I suspect if if I do find enlightenment, I won’t arrive there gracefully but will stumble on it. And, if enlightenment is anything like finally finding answers to the big questions, then I think I’m happy being unenlightened. I enjoy wondering; I love the possibility of not knowing. But I probably do misunderstand enlightenment. Maybe it has nothing to do with answers; maybe it’s more about working out ways to live—ways that cause no harm, bring joy, and allow you the freedom to be who you are. Nothing in that requires you to be able to provide an unassailable answer to any question—in fact, it seems more likely that a question asked will evoke a shrug and a genuine query in response. But maybe that’s just me. Maybe I prefer learning to knowledge. Maybe I’ll always be inclined to answer big questions with a shrug, saying, “I don’t know. Tell me what you think.” And, maybe I’ll always start too many sentences with “Maybe”.

not knowing. But I probably do misunderstand enlightenment. Maybe it has nothing to do with answers; maybe it’s more about working out ways to live—ways that cause no harm, bring joy, and allow you the freedom to be who you are. Nothing in that requires you to be able to provide an unassailable answer to any question—in fact, it seems more likely that a question asked will evoke a shrug and a genuine query in response. But maybe that’s just me. Maybe I prefer learning to knowledge. Maybe I’ll always be inclined to answer big questions with a shrug, saying, “I don’t know. Tell me what you think.” And, maybe I’ll always start too many sentences with “Maybe”.

I returned, unenlightened and happy. Dirk and Miep greeted me; the big house held the heat of the day. What do I long for?

Right here; right now; nothing.

Notes:

1. See Sven Lindqvist’s marvellous, unclassifiable book, Desert Divers. London, Granta. (2000). 144 pp.

Photos:

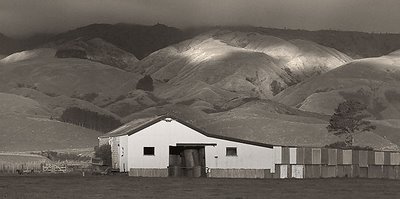

1. Lampshade.

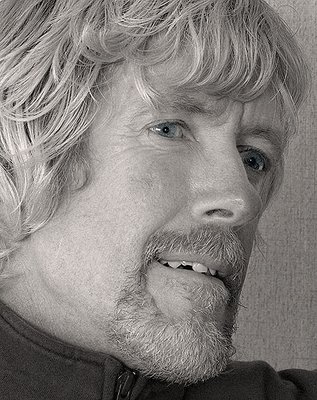

2. Miep.

3. Dirk.

4. Dark phase variable oystercatcher, toreapango, Haematopus unicolor; Eastbourne (Wellington harbour).

5. Red-billed gull, tarapunga, Larus novaehollandiae scopulinus; Eastbourne.

Photos and words © 2006 Pete McGregor