This is an account of a long and eventful day. Some names have been changed, but otherwise it's true, whatever that means. I'm taking a spell from this computer for a few days, so I hope this keeps you satisfied... Oh yes, if you got here by searching for salacious stuff about Anna Kournikova, well... read on... ;^)Last night I slept with Anna Kournikova.

I’d begun the day by dragging myself out of bed after an uncomfortable night, throwing a few essential items and a hefty collection of camera equipment into a day pack and driving off to collect Pat and Josh.  I didn’t even make it onto the main road before having to return to collect my driver’s licence. So much for being on time.

I didn’t even make it onto the main road before having to return to collect my driver’s licence. So much for being on time.

Soon after reaching Palmerston North, I noticed a few drops of rain on the windscreen, and a grey pall advancing across the city from the south. I turned the wipers on to the intermittent setting. A minute later I turned them to continuous; then to fast. By then I’d run out of wiper speeds and was wondering whether I could create an extra-fast setting by forcing the knob to a position it wasn’t designed for. Yes, I thought, a nice day for a walk in the hills. But the rain eased and stopped, and I arrived on time, with the wipers off and still functional. At the door I was greeted by a keen dog and a swarm of enthusiastic small boys.

“Come on in,” Pat said. “Sorry, we’re a bit disorganised.”

That suited me just fine, so I sat in the kitchen, watching in awe as Josh converted an entire loaf of bread into honey and vegemite sandwiches.

“That’d keep me in breakfasts for a week,” I said.

Pat grinned. “You just watch. You’ll be surprised.”

Surprised wasn’t the right word. We drove to the Ballance bridge end of the Manawatu Gorge Track, with Pip sitting happily and quietly in the luggage space and Josh sitting happily and not quietly in the back seat. As we began walking, I realised that one of Josh’s methods of propulsion was talking. I decided to try it, and was pleasantly surprised to find how effective it was. After 20 minutes, Josh indicated that he needed a rest and was getting hungry, so we stopped and he raided the sandwiches, alternating bites of honey sandwich with bouts of talking. The sandwich consumed, we continued walking and talking. He mentioned that his shoulders were uncomfortable because of the weight of his pack, but it wasn’t a complaint, just an observation.

Pat made a rough calculation. “You’ve only got about 3 kg in your pack,” he said.

“How much do you weigh, Josh?” I asked.

He thought briefly. “About 30 stone?” he suggested.

“Let’s see,” I said. “A stone’s 14 pounds. A pound’s 454 grams; roughly half a kilo, so that means about 7 kilos per stone. So, you reckon you weigh a couple of hundred kilos?”

I heard Pat laughing up front. “That’s about two Jonah Lomus,” he said.

Josh realised he’d made a mistake, and began telling us about someone overseas who was four metres wide. I stopped and looked at him. “I’m not even two metres tall,” I said, “so if you stood another one of me on my head and added a bit more, that’s how wide he would be.”

I could see him considering the concept of a four-metre wide person. “Maybe you mean he’s four metres around?” I suggested. “So, if we divide four metres by pi, we’d figure out how wide he is from one side to the other.”

“Mmmm... pie...,” Pat said.

“I like pie,” Josh said. I gave up. Then, “What’s pi?” he asked.

“3.14159...” I began.

“...2654 um...,” Pat continued. Josh looked at us and continued walking. After a few metres he began telling us about 4-leafed clovers and how a friend’s father had found a 48-leafed clover. I showed him pate [1], pointing out the usual pattern of 7 leaflets and the tiny teeth edging them, and kawakawa [2] with its caterpillar-perforated leaves. Later I pointed to a small pate.

“Hey Josh, what’s the name of this one?”

He couldn’t recall the name, but remembered that it was the one with the 7 leaflets. “Hey, this one’s only got 6!” he said. Sure enough, that leaf did only have 6 leaflets. When I asked him to find me a kawakawa he looked about for a few seconds and pointed to a small shrub. “There’s one!” He was right, of course. He then told us all about the structure of the forest; how it had different layers. “The forest floor, the understory, the canopy, and the emergent layer,” he informed us. We discussed the emergent layer for a while; Pat pointing out how awesome it would be to be up there in a South American jungle with all the monkeys and macaws and things, and Josh asking about African jungles.

Partway up an uphill section Pat remarked on how this was getting the heart working.

“I reckon my heart must be beating every half a second,” Josh said. Not a bad estimate for an eight and a half year old (actually, eight and three quarters, as he later told me).

“Your heart’ll be getting strong, doing this,” Pat said.

Josh liked that idea. “We should do this at least once a week,” he said. He was keen on the idea that his muscles would  get strong, and—ignoring the fact that the only exercise his arms were doing was providing visual emphasis for the exercise his vocal cords were getting—showed us his biceps. We admired the size of his biceps, then, in response to his query, tried to explain why you’d live longer if your lungs stopped working than if your heart stopped beating, or if you didn’t have a heart at all.

get strong, and—ignoring the fact that the only exercise his arms were doing was providing visual emphasis for the exercise his vocal cords were getting—showed us his biceps. We admired the size of his biceps, then, in response to his query, tried to explain why you’d live longer if your lungs stopped working than if your heart stopped beating, or if you didn’t have a heart at all.

By this time my credibility had begun to erode because I’d kept suggesting we weren’t far from the lookout where we could have lunch. Fortunately, we arrived there before Josh had written me off completely—Pat had done that ages ago, but he doesn’t matter. The Department of Conservation had recently erected a wooden bench seat so we (the Department of Conversation) sat there and ate lunch. At least, Pat and Pip and I sat—Pat and me on the bench, Pip directly in front of me where he could examine in minute detail the bier stick I was eating—while Josh sat, talked, ate, jumped up to take a photo while talking, sat down (also while talking), ate, talked, jumped up to check something, continued talking, and ate (between spells of talking).

“Where are the vegemite sandwiches?” Pat asked.

“I made some. I made honey sandwiches and vegemite sandwiches,” Josh replied.

“You made ONE vegemite sandwich.”

“It’s hard to spread vegemite on butter.”

“Yep, it just skids over the butter. You end up with skid marks on your sandwich,” I said.

“Ewww, gross,” Josh said, and continued eating.

I’m not sure who eventually got the one vegemite sandwich, but Pat’s prediction that I’d be surprised at how the enormous stack of sandwiches would disappear proved correct,  albeit understated. Within minutes, they’d all been eaten. In the distance, a kereru soared high above the canopy, stalled, then swooped down. It repeated the manoeuvre several times and I pointed it out to Josh, who immediately spotted another one. Pip snuffled at my pack, tantalised by the aroma of bier stick; across the gorge, a battalion of huge windmills churned like alien invaders in a post-apocalyptic world. We could hear the roar of a nearby windmill on our side of the river: background noise to the rush of the wind-whipped vegetation and the drone of an aeroplane. Pat scanned the lumpy cloud.

albeit understated. Within minutes, they’d all been eaten. In the distance, a kereru soared high above the canopy, stalled, then swooped down. It repeated the manoeuvre several times and I pointed it out to Josh, who immediately spotted another one. Pip snuffled at my pack, tantalised by the aroma of bier stick; across the gorge, a battalion of huge windmills churned like alien invaders in a post-apocalyptic world. We could hear the roar of a nearby windmill on our side of the river: background noise to the rush of the wind-whipped vegetation and the drone of an aeroplane. Pat scanned the lumpy cloud.

“Let’s see who can spot the plane first.” Soon after, he saw it and pointed it out. Josh spotted it shortly after. I kept looking, but couldn’t locate it.

“Over there, next to that mushroom shaped cloud,” Pat said, pointing to a sky full of mushroom shaped clouds.

“I can see it!” Josh yelled, pleased not to be the last. I never did see it.

At the next lookout point, Josh decided he wanted a photograph of the Manawatu gorge with cars and trucks winding along the road. He put his eye to the viewfinder and began composing the shot, so I jumped in front and pulled a face.

“You need people in the photo,” I said.

He laughed and waved me away. “Getoutofit!”

So I got out of it.

He seemed to be having trouble with the composition. “That pine tree’s in the way,” he said.

I looked where he was pointing. “That’s not a pine tree. That’s a horoeka [3]; a lancewood. They’re cool trees; when they get big they get really gnarly. You want one of those in the photo.”

It seemed to do the trick, and he took a photo with the horoeka in the foreground. We walked on, surprised by the lack of windfalls on the track. Josh saw a giant epiphyte high in a big rimu and pointed it out.

“Collospermum [4],” Pat said. Even from a distance, its size—perhaps 1–1.5 metres diameter—suggested something enormously heavy.

“You wouldn’t want that to fall on you,” Josh said.

“Yeah, some of them weigh a tonne or more,” I said. “If it fell on you your eyeballs would shoot 20 metres.”

Josh was intrigued by the concept, and wanted to know whether you’d still be able to see out of them. We discussed diverse scenarios involving eyeballs at various distances from their sockets, attached, or not, or reattached, to their optic nerves and the circumstances under which you might be able to see, or not. Josh considered experimenting but we dissuaded him, pointing out that although it might be a good excuse for not doing your homework—“I’m sorry Mrs Krabapple, but I couldn’t see where my pencil was ‘cos my eyeballs were somewhere else”—it would likely make life difficult if the attempt to reconnect eyes and optic nerves failed.

attempt to reconnect eyes and optic nerves failed.

Near the end of the track, Pat and Pip jogged on ahead to meet Kate and Jack and Lee and reassure them we were ok, as we were running late (it had the opposite effect, when Kate saw Pat running down the track with no sign of Josh and me: she naturally assumed something bad had happened). Josh and I walked on, talking, and eventually decided we’d jog too. We ran downhill, spinning around corners and leaping patches of mud and continuing our conversation, which mostly comprised a discussion of how to run downhill without face-planting. We met the others about 10 minutes from the car and Josh immediately began a detailed description of the day’s events.

Pat looked at me, then grinned at Kate, and said, “I think I’ve at last found someone who talks as much as Josh.”

We negotiated the short section of streambed, Jack and Lee happily scrambling barefooted over the rocks and gravel, climbing the footbridge railing and hanging over to look at the little waterfall. If there was a longer, more difficult route that involved climbing something and getting covered in dirt, they took it. My kind of kids.

Kate drove us back to my car, the kids in the back seat and Pat huddled in the luggage space with Pip. Josh thanked me for coming tramping with them.

“A pleasure, Josh. We’ll do it again.”

“Yeah, once a week!”

...

That evening I took the back road to Palmerston North to meet Dee and Ian. The sun still hung well above the horizon; a kahu circled over a freshly cut hay paddock. A few kilometres beyond Ashhurst, a weasel ran across the road. The Lombardi hadn’t yet reopened for the new year, so we headed for the Celtic but too many loud conversations were already in progress. Eventually we settled at a table outside the Mao Bar and talked over a Monteiths until it got too cold. We moved inside, upstairs, and resumed the discussion—a wide-ranging conversation about how to save the world, about how to influence attitudes, about information and understanding, about noticing things and how to describe them. When someone turned the music up, signifying the start of revelry and the end of meaningful conversation, we drove to Pacha’s to pick up kebabs. He recognised Dee and Ian and began conversing with them in French, then indicated a friend who had stepped outside for a smoke.

“Odile!” he called, and introduced him. I sat there, delighted, understanding nothing except the occasional “oui,” or “vous.” Pacha apologised for my exclusion from the conversation, but I didn’t feel excluded—for me, it was enough to see and hear the enjoyment and animation of the dialogue. People having fun; friends communicating.

After collecting our kebabs I drive us back to where Dee and Ian were house-sitting. We watch Darwin’s Nightmare, a desperately grim, almost savage documentary about an African village surviving—if that’s the right word—on a fishing industry based on Nile perch. Some of the conversation is in Swahili and Russian, with subtitles in French, so Dee translates for me. A man places a basin of food on the ground, and instantly it’s an explosion of hungry children, fighting, grabbing handfuls, running, stuffing the porridge-like food into their mouths, trying to protect what they have, punching, wrestling... A security guard, armed with a bow and poisoned arrows, tells how the previous guard was murdered. A thin young man in camouflage pulls a boy along by his sleeve and punches his face. A woman stacks the filleted remains of fish on racks to dry; she’s surrounded by a sea of racked, rotting, shrivelling fish and she stands in a writhing mass of maggots. The stench must be unimaginable, but she doesn’t complain—she has work, she explains. The ecology of the lake has been destroyed; in its murky, algal depths, the only fish now are the Nile perch. Someone says the perch survive by eating their young. The factory manager says they harvest 500 tons a day, it’s exported on two flights a day but each flight carries only 55 tons. What is true? This is a nightmare; this is Hobbes’ vision: “And the life of man: solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” What can be done?

It’s half past midnight and I’m shattered. Dee sets me up in a spare room; I toss my sleeping bag on the bed, clean my teeth, take out my lenses, and crawl into the bag. I look up and realise I’m sleeping with Anna Kournikova, but I’m too tired to enjoy it. Besides, I’m also sleeping with a giant Brontosaurus.

Notes:

1. Schefflera digitata

2. Macropiper excelsum

3. Pseudopanax crassifolius

4. Commonly called a “perching lily”.

Photos 1 & 2: A few days ago, just on dusk, we had a rain squall so loud I could hardly hear myself think. It stopped suddenly, and this is what the evening looked like.

Photo 3: Spurwinged plover; Vanellus miles novaehollandiae. This is a cropped and resampled image—these birds are very hard to approach.

Photo 4: Yep, it is indeed a house sparrow. Quite an old photo, from Whitewash Head near Christchurch, about this time last year.

Photo 5: This is the peculiarly flattened jumping spider, Holoplatys sp. Photographed on my verandah.

Photos and words © 2006 Pete McGregor

The interior of the car’s like an oven and turning the fan on does nothing but turn it into a fan oven. I’m close to expiring, or at least melting into a grease puddle, but I console myself with two thoughts: that the lack of air conditioning means I’m saving fuel and thereby the planet; and heat and humidity like this is good preparation for India later in the year.

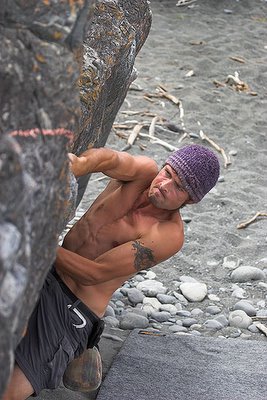

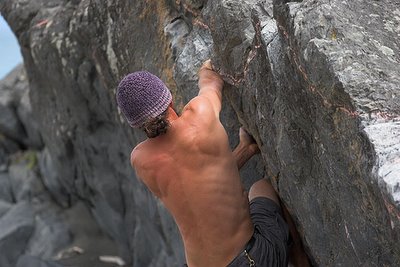

The interior of the car’s like an oven and turning the fan on does nothing but turn it into a fan oven. I’m close to expiring, or at least melting into a grease puddle, but I console myself with two thoughts: that the lack of air conditioning means I’m saving fuel and thereby the planet; and heat and humidity like this is good preparation for India later in the year. He’s just set a big fishing rod in its holder, closer to the surf; the tip vibrates very slightly as the sea pulls at it. I wish him luck and get another smile. Close to the boulders, two big women arrange picnic gear while a man sets up a rod, flinging the tackle far out into the slow-heaving sea. Everyone’s friendly and happy today. I see the silhouettes of small figures hopping along the top of the Long Wall, dark forms against the salt-hazy sky and wonder if any of the fishers have any idea what all the crazy people are doing scrambling over those rocks.

He’s just set a big fishing rod in its holder, closer to the surf; the tip vibrates very slightly as the sea pulls at it. I wish him luck and get another smile. Close to the boulders, two big women arrange picnic gear while a man sets up a rod, flinging the tackle far out into the slow-heaving sea. Everyone’s friendly and happy today. I see the silhouettes of small figures hopping along the top of the Long Wall, dark forms against the salt-hazy sky and wonder if any of the fishers have any idea what all the crazy people are doing scrambling over those rocks.  Looking up from the ground is seldom a good choice—a wideangle lens foreshortens the climb, reducing its apparent height and steepness; and wideangle shots of climbers’ bums are, well, ... I suppose you could use them to poke fun at your mates—or, perhaps, to make lifelong enemies.

Looking up from the ground is seldom a good choice—a wideangle lens foreshortens the climb, reducing its apparent height and steepness; and wideangle shots of climbers’ bums are, well, ... I suppose you could use them to poke fun at your mates—or, perhaps, to make lifelong enemies. I notice it again when I’m photographing John, Peter, and Dan taking turns working hard on Chris and Cosey, one of the hardest problems at the Head—I’m dangling from one hand, Tevas on tenuous footholds, photographing with the other hand; I lower the camera and realise I’m mere inches away from John as he’s heading for the next hold. I hope I haven’t distracted him, so console myself by believing he’s putting in an extra-special effort just to look heroic for the camera.

I notice it again when I’m photographing John, Peter, and Dan taking turns working hard on Chris and Cosey, one of the hardest problems at the Head—I’m dangling from one hand, Tevas on tenuous footholds, photographing with the other hand; I lower the camera and realise I’m mere inches away from John as he’s heading for the next hold. I hope I haven’t distracted him, so console myself by believing he’s putting in an extra-special effort just to look heroic for the camera.  Maybe, without realising it, what we’re doing when we’re bouldering, or climbing in most forms, is really a kind of dynamic meditation.

Maybe, without realising it, what we’re doing when we’re bouldering, or climbing in most forms, is really a kind of dynamic meditation.